In the early days of Las Vegas, restaurants were considered an operational function to feed gambling customers, with the emphasis on low prices and high quantity. The customer could dine at the 24-hour café, the deli, the steakhouse, potentially a Chinese or Italian restaurant (if it were an upscale joint) and the ubiquitous Las Vegas buffet. The marketing benefits of fine dining appeared in the early 1960s, with the advent of the gourmet room, a 30 to 50 cover restaurant that was full of gamblers eating comped meals, and used as the hors d’oeuvres to the entertainment offering that was the real attraction of the evening.

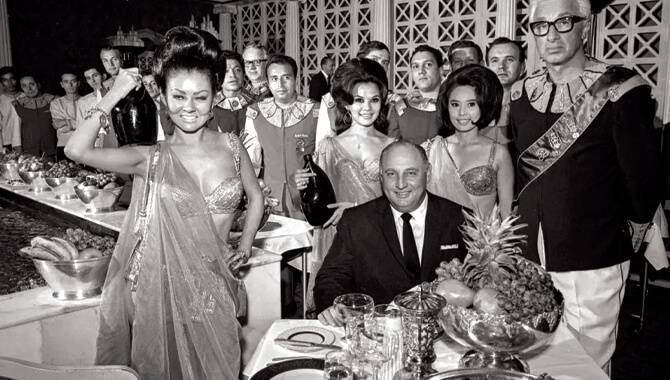

Notable gourmet rooms included The Sultan’s Table at The Dunes and The Candlelight Room at The Flamingo. Some properties grew to have multiple gourmet rooms, however it was the experiential dining centerpiece, The Bacchanal at Caesars Palace, led by acclaimed Las Vegas executive Nat Hart, that ushered in a new era. As part of the highly themed property, toga wearing servers dropped grapes and poured wine as diners enjoyed dishes, such as Beach Port Lobster Tail, Armoricaine, Broiled Prime Filet Mignon Caesar Augustus and Prime Colossus Sirloin Steak Pompeii. Although a minimum spend of $12.50 per person was required, over half of the tabs were picked up by the casino on behalf of their customers. The Bacchanal closed in 2000, 34 years after opening.

Nat Hart personally opened over 30 restaurants in Vegas, LA, Atlantic City and other global markets. He is created as the creator of corporate food and beverage (F&B) within the casino context, creating a structured program for Caesars World, where he led F&B for over 20 years, personally writing the training and operating manuals, which formed the template across the industry. He died in 1995 and his influential works can be found at The UNLV as the Nat Hart Professional Papers.

Other than Hart’s standardizing and formulating the gourmet platform, the next great innovation in casino dining came in 1984 in what gaming historian David Schwartz called, “The Burger King Revolution.”

Jeff Silver, noted gaming attorney at Dickinson Wright and regular contributor to Gaming America, was the lead executive at The Riviera during the 1980s. “At that time, The Riviera had neither the bankroll, nor the facilities to compete for the high-end customers. What it did have was the cache of old Vegas and the reputation for offering a quality product at a fair price. Many of its customers were older, loyal repeat guests. To entice a younger crowd, I added a hip musical revue, Solid Gold, and began to examine our restaurant offerings. I saw there was a corporate-owned McDonalds flagship store across the street next to CircusCircus. It always had lines of customers. This was despite the invitation on the CircusCircus marquee offering their Plate of Plenty buffet for $1.99, all you can eat. Then it struck me that visitors really wanted familiarity, consistency and price. What better way to entice them than for the two preeminent US burger chains to go head-to-head on the Las Vegas Strip. The food court concept in a casino was born, anchored by the most successful Burger King outlet in the history of that chain.”

Silver’s move to bring in external brands directly into casinos was both controversial and popular, as fast-food outlets and national restaurants began to find homes inside casinos.

Enter The Chefs

Although in decline, the traditional template for restaurants set out by Hart was still in place as the megaresort age began with The Mirage in 1989. The property had a portfolio of uniquely branded restaurants, all operated by the resort, including the much-missed Kokomo’s. The dining revolution was to occur next door in December 1992, as Wolfgang Puck opened a satellite to his famous LA hotspot, Spago in The Forum Shops.

John Curtas, the Las Vegas based food critic, author of eatinglv.com and local celebrity in his own right, observed the period.

The common historical narrative credits Puck with being the ripple that started the celebrity chef tsunami. But in reality, it was Gamal Aziz, F&B VP at MGM, who made the biggest splash. His 1994 “murderers row” of Charlie Trotter, Mark Miller, and Emeril Lagasse (at The MGM Grand) brought immediate culinary credibility to Las Vegas, and the international press they garnered got every other casino’s attention.

Keep in mind, all of this paralleled the rise of the Food Network, which reflected the revolution, started in the 1980s, of the way America was starting to think about better food and restaurants. Good restaurants were worth aspiring to, and Baby Boomers, aspirational by nature and in their prime earning years, were demanding better dining options.

Thus Las Vegas became the perfect Petri dish for the celebrity chef phenomenon: hordes of Boomers with cash to spend at branded restaurants, opened by newly minted culinary gods, courtesy of the Food Network’s star making machine. Steve Wynn grasped this first, bringing Todd English, Le Cirque, and others on board at The Bellagio, and then Hubert Keller, Charlie Palmer, et al at Mandalay Bay, and Thomas Keller and Mario Batali at the Venetian weren’t far behind.” The trailblazers’ successes led to every famed chef and restauranter to believe that the boulevard was paved with edible gold leaf, as Ogden, Savoy, Robuchon and Ducasse were joined by Ramsey, Giada and Flay, and Carmine’s, Joe’s and Rao’s either with new concepts or Vegas sized offerings of their flagship outlets.

This celebrity chef pattern continued as the dominant strategy. But as younger, metropolitan, urban customers, rather than boomers, were making their way to Las Vegas, the offering began to follow. Tao, Hakkasan, Lavo, Nobu and STK, all F&B/nightlife brands, identified Las Vegas as a potential outpost for the new wave of cool, each opening to great success.

The immediate impact of the cool crowd, exemplified by the opening of the The Cosmopolitan in 2010, was evident, as resorts again repurposed their offering with experiential eateries such as Carbone, Sushi Samba, Catch, Best Friend, Momofuku and Zuma making their way to town.

Like highly prized performers, hosts and DJs, restaurants began to move properties as their leases expired: Puck’s Spago went to The Bellagio and Milo’s to The Venetian, moves unimaginable a generation earlier.

As the second decade of the new century closed, The Las Vegas Strip was clearly established as one of the leading dining destinations in the world.

Food For Thought

In 1973, Bill Friedman published a book based on his then revolutionary class taught at the new UNLV. Casino Management remains a bible for all those who wish to study the industry, but an omission remains as relevant as the remaining content. There is virtually no mention of food and beverage, other than as a note within marketing and a guide to comping. In this respect, Friedman was correct, F&B is a vital marketing component both for existing and potential customers and as a clear differentiator, but he had not envisioned how important it would grow to be.

In 2018 research, we observed that only 30% of Las Vegas visitors definitely spend most of their F&B budget in the property that they were staying in, with 49% spending the majority in another property and 21% were unsure.

It’s important to track the evolution of F&B in the operational context. In 1995 F&B on the Strip actually lost casino operators $35m, such was the level of discounting and comping. Gross F&B revenues on The Strip in 2019 were over $4bn and assuming a market margin, this would see total restaurant profits at over $800m.

F&B revenues accounted for 24% of all customer spend in Las Vegas in 2019, compared to 19% in 2005. Looking at individual spend per trip across Las Vegas, between 2005-2019 gaming spend per visitor rose from $139.41 to $152.76, a 9.6% increase. F&B spend grew from $66.46 to $104.44, a 57.1% over the same period.

No doubt the diverse and improved F&B offering contributed to the changed perceptions of the city, added to the total revenue mix, and assisted to the change in visitor demographic.

Soup To Nuts?

In post-Covid Las Vegas, the evolution of restaurant operations is moving into another interesting phase.

In the days of Nat Hart, the casino resort operated everything as they provided their customers with the 360-degree experience under one roof, where servicing the gaming customer’s needs with the incentive to stay and play as the main deliverable. Restaurants were unique brands and everything from chefs to servers provided was internal. Efficiencies could be made by central kitchens, put under the floors of the restaurant in many of the newer properties, and throughout multiple outlets with common staffing and training operations. When a celebrity chef was attached to the project, they would typically license their name and brand, create the menu and suggest key hires, but all the staff would be employees of the casinos. The economics would be that the casino provides the capital, and the third party would receive a varying percentage of the top line and bottom line, depending on performance.

A second, non-traditional model, employed by Puck and exploited by the Venetian in 1999, saw restaurants take leases within casinos, with the casino playing the role of landlord, generating revenue without the operating liability. This allowed specialist restaurant operators to come to market and deliver a range of product that would align with the property, satisfy the customer and benefit the casino with lower levels of investment and risk. The capital contribution would typically be split by the casino (by way of a traditional tenant allowance seen in many leasing deals) with remaining capital paid by the restaurant operator, who received the profit.

In the case of the Venetian and Palazzo, on any given day, 12,000 individual customers are staying on property for an average of four nights. Diners are a mix of leisure and business customers, spending more than they would do in a home environment. With such high transition, successful restaurants have significantly increased longevity for their business. For a third-party operator, this is a better location than any major city has to offer.

The first two models are the simple binary options. However, as gaming operators trend toward Opco/REIT structures, a variety of novel deal and lease structures are being created. This is potentially beneficial for all parties, as in some of these deals, casinos are potentially leasing space out at or below market rates, thus reducing the exposure for restauranters, but with the casino operators claiming a higher share of the revenue and profits, capitalizing on the increased spend on F&B and customer REVPAR. In some cases, particularly in more progressive properties, the restaurants are actually joint ventures or partnerships between property and restaurateur, where capital costs are shared and profits mutually distributed. In more sophisticated properties, restaurants are implementing dynamic pricing, or where pricing varies dependent on time, date and demand.

Leftovers

An interesting byproduct of the past 30 years and the emergence of culinary culture in Las Vegas is that many talented chefs and restaurateurs who have grown up in this exciting marketplace have been left frustrated with the corporatization of the deals, high barriers to entry and decline in opportunity for innovators and chefs to exercise their flair and imagination within Las Vegas casinos’ narrow strategies.

As a consequence, some executives now export their expertise to other markets and clients, such as former Wynn and MGM executive Sean Christie’s new Carver Hospitality and former Wynn and Cosmopolitan executive Olivier Zardoni’s 34th Floor, and many have opened their own places outside the casino corridor, in The Arts District, Chinatown or in suburban neighborhoods.

Locals, fed up of car parking charges and traffic bottlenecks on The Strip, are flocking to former Mirage, Bellagio and Caesars Palace chef, James Trees’ Esther’s Kitchen and Al Solito Posto, and the assorted Strip alumni that operate the acclaimed Sparrow+Wolf, Honey Salt, Partage, The Black Sheep, Forte Tapas and many others, all of which would more than hold their own in a resort setting.

And the tourists are noticing, leaving the Strip to explore previously unheralded parts of the city to sample innovative experiences.

As Vegas has rightly developed a global reputation for excellence in hospitality, gaming, entertainment, conventions, sport, events and nightlife, the culinary aspect is sometimes overlooked. It shouldn’t be. At a time when restaurants around the world are closing, Las Vegas has new places opening weekly, bringing the best brands, cooking and chefs on the planet, all in an accessible environment, as well as curating and supporting local talent. Who else can say that? Not Paris, not London, and certainly not New York.